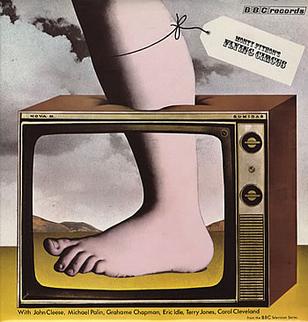

“I think all the Pythons are nuts in some way,” Eric Idle once wrote, “and together we make one completely insane person.” That insane entity, the comedy supergroup Monty Python, convened in 1969, with the BBC sketch show “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” Its six members—Idle, John Cleese, Michael Palin, Terry Jones, and Graham Chapman, plus a lone American, Terry Gilliam—became the defining absurdists of postwar Britain, stomping their collective foot on polite society. You know the rest: the ex-parrot, the Comfy Chair, the Ministry of Silly Walks, the Knights Who Say “Ni!” If he had done nothing else, Idle would have given humanity an enduring gift with “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,” the ditty that ends “Monty Python’s Life of Brian,” sung by a group of unlikely optimists while they’re being crucified. At one point, it was ranked the most played song at British funerals.

But Idle’s work extends beyond Monty Python. His TV film “The Rutles: All You Need Is Cash,” from 1978, which chronicles the rise of a not-quite-the-Beatles rock band, was an early specimen of the mockumentary. (A sequel, “The Rutles 2: Can’t Buy Me Lunch,” appeared in 2003.) Based in Los Angeles since 1994, Idle has lent his trademark jolly obnoxiousness to everything from the English National Opera’s production of “The Mikado” to the reality show “The Masked Singer.” With his musical partner, John du Prez, he wrote “Spamalot,” a stage musical “lovingly ripped off” from “Monty Python and the Holy Grail,” which won the 2005 Tony Award for Best Musical and was revived on Broadway last season. Idle and the surviving Pythons—Chapman died in 1989, Jones in 2020—are now beloved octogenarians, the closest thing comedy has to living deities.

And yet there have been signs of disquiet in the Python kingdom. The group’s most recent (and, they insist, final) reunion was a decade ago, at London’s O2 Arena, and was motivated less by fan service than by financial straits. A producer of “Holy Grail” had successfully sued for “Spamalot” royalties, claiming that he’d been the “seventh Python.” (Idle called the idea “laughable.”) This past February, Idle tweeted about the Pythons’ money problems—“I never dreamed that at this age the income streams would tail off so disastrously”—and pointed the finger at their asset manager, Holly Gilliam, Terry’s daughter. Cleese came to Holly’s defense, calling her “very efficient, clear-minded, hard-working, and pleasant.” The two men, who had toured together as recently as 2016, traded barbs on X: Idle revealed that he hadn’t seen Cleese for years; Cleese posted, “We always loathed and despised each other, but it’s only recently that the truth has begun to emerge,” then said that he was joking. Still, fans wondered: Had the Spam soured?

…

There’s a line that stood out to me from the diary: “On a positive note, I did realize this morning that the Grail is essentially about the Pythons: each knight’s character is a reflection of our own.” Can you tell me what that means?

You know, John Cleese is Lancelot, and he’s violent and keeps smashing people to bits. Michael Palin has got an eye for the girls, but he mustn’t do that. I’m Sir Robin, a friend of the musicians. Terry Jones is Bedevere: a bit batty, with odd theories. And Gilliam’s a kind of daft Patsy.

…

In your “sortabiography,” from 2018, you write that, decades after “Holy Grail,” you were working on a sequel, “The Final Crusade,” and John Cleese didn’t want to do it.

Yes, in the end it was John. Funnily enough, I’ve got a little booklet of it, which I’m taking on tour to sell in the lobby. It’s called “Almost the Final Python Film: The Not Making of The Final Crusade.” I had this idea, and I wrote a little treatment. I go and see John, and we have a pleasant lunch in Montecito. He likes it, so I send it to all the others. We all meet in Cliveden, which is a hotel on the Thames owned by the Astors. And John announces that he doesn’t want to do it. Then Gilliam says, “Could you have mentioned this before we all gathered here?” [Cleese, who has a different memory of these events, says that he never thought the movie was a good idea, and still doesn’t.]

I liked the idea that we would all play the same knights, but twenty years have passed, and we would be much older and grumpier. They want us to take Arthur’s body back to the Holy Land, and Graham could still play Arthur: we could use vocal technology to have him say any lines we wanted from inside the sepulcher. I loved the idea of Graham complaining, “Get on with it!”

…

Back in February, there was this exchange between you and John Cleese on X that got a little testy, but maybe tongue-in-cheek. How is your relationship with John?

Well, I would say poor. I’d been unhappy with the business and how it was working. And they aren’t unhappy. It’s odd with John, because things started to go a bit south during lockdown, and I got worried. I haven’t seen him for eight years. I think when you lose touch with people face to face, all sorts of things can happen. It’s a pity. It’s not how we were. Again, I met him in 1963, so that’s an awfully long time. I’ve known many versions of John: times of happiness, times of sadness, times of success, times of less success. You just have to take a long view. We don’t have to force each other to face each other on everything that has to be decided. I try not to get involved if I can, because I feel very lucky that I’ve survived. [Idle was given a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer in 2019, but it was treated successfully.] I had a reprieve, and you shouldn’t spend the rest of your time bickering if you’ve had a reprieve.